The regulatory use of real-world data (RWD) in clinical trials is rapidly growing, and regulators are reviewing and inspecting RWD-based submissions with the same scrutiny applied to traditional clinical trials. At the 2025 DIA Real-World Evidence Conference, that message was front and center in a session chaired by Dr. Motiur Rahman (Senior Epidemiologist and Policy Advisor, Real World Evidence Analytics, CDER, FDA). The session featured talks by Dr. Kassa Ayalew (Director of the Division of Clinical Compliance Evaluation, Office of Scientific Investigations, CDER, FDA),and Dr. Mayur Saxena (CEO, Droice Labs), who both focused on review and inspection of RWD in FDA submissions, and a talk by Kirk Geale (CEO, Quantify Research) that described the use of Nordic RWD to support pharmacovigilance for EMA.

The talks and discussions by Ayalew and Saxena focused on a simple question that now sits behind every RWD program aimed at FDA: what does it actually mean for real-world evidence (RWE) to be ready for FDA review and inspection, and how should sponsors and their partners design and execute RWD-powered clinical trials that meet that bar?

The same evidentiary standard for RWD as clinical trial data

From the outset, Rahman was clear that RWD does not get a pass simply because it comes from routine care rather than a traditional randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Ayalew reinforced the point from the inspection side. He emphasized that FDA still expects quality and compliance at the same level as RCTs.

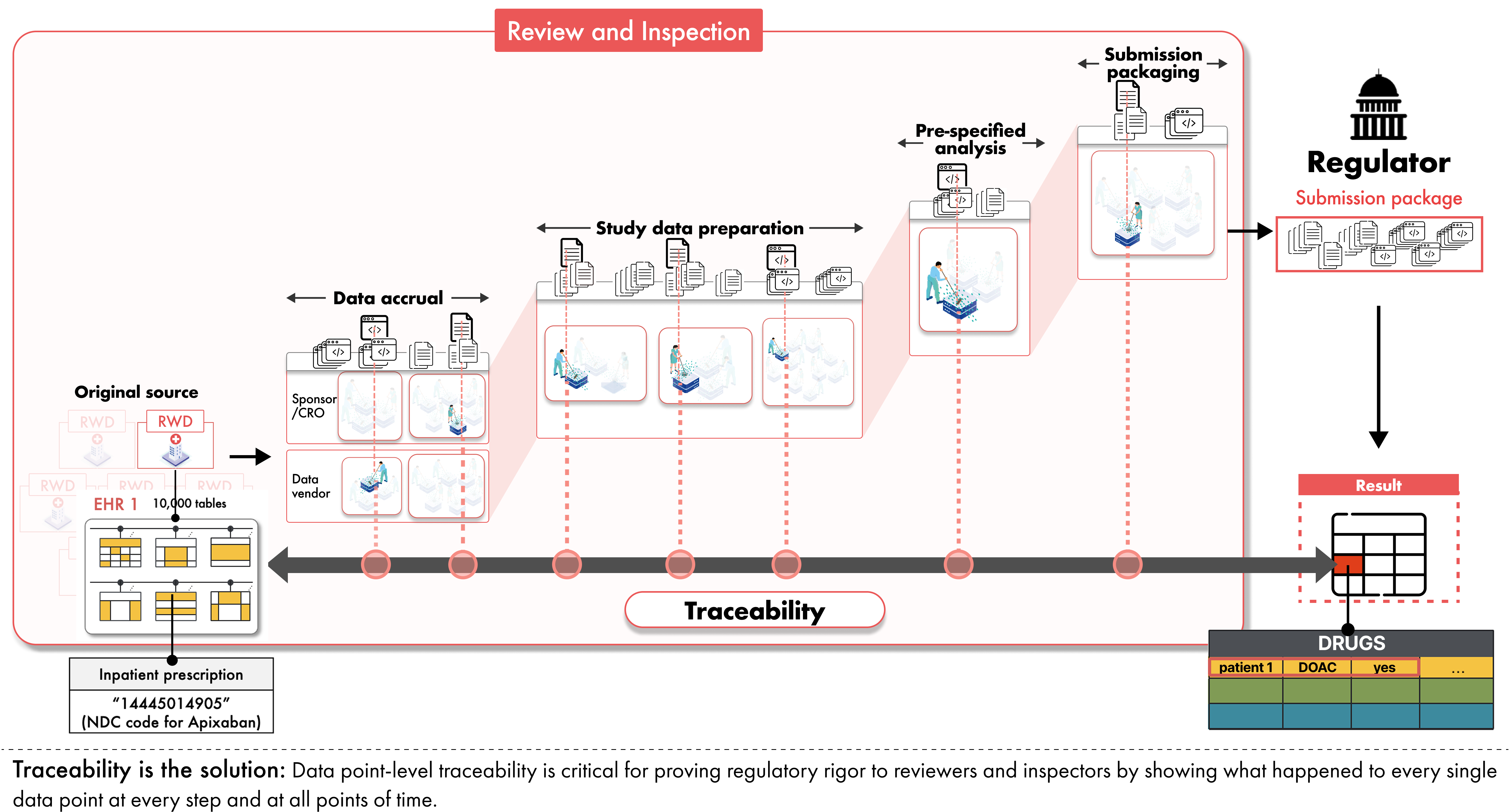

Inspectors focus their investigations on whether the data are reliable and relevant for the question at hand, whether privacy and confidentiality are protected, and whether data integrity is preserved across the full data lifecycle from acquisition at the original data source through analysis and reporting. He noted that sponsors are responsible for oversight at each step from source to submission, not only at the point of analysis. This means that sponsors must ensure complete traceability and auditability from the original source data (e.g., the original EHR where the clinician documented the patient data) to the submitted data and analyses.

Where RWD submissions face challenges in inspection

Ayalew described recurring issues that arise when RWD is used in regulatory submissions through a discussion of real-world examples of inspection issues faced by FDA in RWE submissions. Inspection teams often encounter limited access to source records, inconsistent collection methods, a lack of traceability and data lineage tracking, and missing or inadequate third-party data use agreements.

In one example, a sponsor built an external control arm for a clinical trial from an international registry curated by a third party. On paper, the study design looked reasonable. When FDA attempted to verify the analysis, however, they found that informed consent for this specific use had not been obtained and no agreement allowed FDA access to the underlying records. Months of delay followed while the sponsor negotiated data use agreements, addressed local ethics requirements, and obtained de-identified certified copies of the original records. Only then could FDA confirm that the external control data matched what had been submitted.

The takeaway is straightforward: FDA cannot rely on evidence it cannot verify. If inspectors cannot see and check the underlying data, the study may be delayed or rejected, regardless of the sophistication of the design or analysis.

RWD is not the same as RCT data

Saxena described why it is that even well-designed RWD studies can run into major problems if sponsors do not address the fundamental differences between routine care data and protocolized trial data.

“We all know RCTs are the gold standard for evidence, especially regulatory,” he said. “We also know RWD is not RCT data.”

For example, in RCTs, patients visit on a set schedule and their predefined study-specific variables are collected in a standardized manner. However in RWD, patients present as and when care is needed, and how patient information is documented varies widely across clinicians and sites. As a result, RWD must be transformed far more extensively than RCT data on the journey into study analysis datasets compliant with FDA submission standards. This results in two major issues with RWD: inherent bias and lower data quality. Saxena noted that while the field has made significant strides in addressing inherent bias through modern clinical trial study designs such as pragmatic and hybrid-controlled designs and randomized registry trials, lower data quality remains the main reason that promising RWE programs encounter problems under review and inspection.

Why it’s critical to measure data quality for the study at hand

Saxena emphasized that the issue is not whether a data source is “high quality” in an abstract sense, but whether data quality is sufficient for a specific study design and its specific variables.

Furthermore, he noted that it’s critical to measure data quality for the actual data being used in a study and not reuse historical data quality measures from the same sources. This is because even within a single health system, data quality of study variables can vary drastically over time for reasons such as changes in documentation patterns, clinicians, standards of care, or IT systems.

Saxena then broke data quality into two practical dimensions that align with how regulators think about it. Completeness is an assessment of missingness (i.e., for a given exposure, covariate, or endpoint, whether there is adequate information available to confirm or deny a variable), and accuracy is an assessment of the amount of error.

He further stressed that accuracy and completeness should be measured against the original source, and not against an aggregated registry or common data model layer, since any transformation from the original source can introduce unknown and non-random information loss and error.

Data quality embedded study design

The panel emphasized that data quality isn’t measured simply for the sake of characterizing data accuracy and completeness – these data quality measures should drive the way studies are designed and executed. Saxena described what he called “data quality embedded design,” where study decisions and analyses are explicitly tied to the study-specific data quality metrics in a prespecified manner.

Once completeness and accuracy are quantified for the specific study variables, the protocol and statistical analysis plan should describe how data quality will be taken into account. For example, prespecified quantitative bias analyses can be used to evaluate the impacts of error on the final results.

“It is not enough to measure data quality,” Saxena said. “You have to use it to drive design decisions.”

How FDA inspectors evaluate RWD submissions

Ayalew highlighted that FDA inspectors expect to see how prespecified protocols and analysis plans address data quality, and that sponsors follow those plans once the study is underway.

To make these expectations more concrete, Saxena highlighted recently published work by Ayalew and colleagues from FDA’s Division of Clinical Compliance Evaluation, Office of Scientific Investigations (OSI), CDER, and other FDA authors from the Offices of Regulatory and Medical Policy and Oncologic and Rare Diseases. This paper, Keeping the End in Mind: Reviewing U.S. FDA Inspections of Submissions including Real-World Data, describes critical activities FDA inspectors perform when evaluating RWD submissions to FDA. For example, FDA reviewers and inspectors:

“Verify critical RWD submitted to support the regulatory decision against the source records to ensure that the data submitted to FDA match the source records”

“Assess RWD for appropriate level of data quality and reliability (e.g., attributability, accuracy, consistency, completeness, and traceability)”

“Assess study conduct to ensure protocol-related plans (e.g., statistical analysis plan, data management plan), and processes and procedures for data extraction, curation, transformation, and analysis were followed as pre-specified”

Traceability is critical for review and inspection

Even when design is sound and data quality is measured, RWD-based studies can fail inspection if the entire execution is not traceable. RWD typically passes through numerous hands on the journey to a submission: health systems, data aggregators, vendors, and analytics teams. Each step introduces potential for error. The only way to maintain confidence in the data accuracy and integrity is to preserve clear and comprehensive traceability across the entire data lifecycle, from source to submission.

Ayalew explained that inspectors want to ensure that the data are complete, traceable, and free from manipulation. Saxena translated that requirement into a practical test for sponsors:

“Let’s say I have a result in my submission package, one data point for one patient,” he said. “How exactly did it come from the original source into this final form that was submitted? What was done to it? Where was this done? With which tools, which code, which process?”

Traceability means being able to answer those questions. For any result in a submission, regulators should be able to see which source record it came from, how it was extracted, transformed, and analyzed. When that chain is clear, inspection becomes a matter of checking the work. When it is not, regulators have little choice but to question the reliability of the evidence.

Reliability = Data quality + Traceability

Across the session, FDA’s definition of reliability emerged: reliable RWD is data with quantified quality plus traceability. Saxena summarized it succinctly: “Data quality and traceability together define reliability. And reliability is exactly what the FDA asks for.”

How Droice supports inspection-ready RWE

The panel session made clear that reliable RWD for regulatory decisions requires two things: quantified data quality that is sufficient for the study at hand and full traceability from source to submission. Droice’s AI middleware technologies are built to deliver exactly that combination at scale.

Droice Hawk automates the transformation of complex RWD from clinical sites, commercial vendors, registries, claims, etc. into high-quality data for regulatory submissions. Droice SuperLineage records comprehensive traceability for each and every data point from the original source through extraction, curation, and transformation into SDTM and other submission-ready datasets, all in full compliance with privacy regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR.

About Droice

Droice helps biopharma generate robust evidence for FDA, EMA, and other regulators with modern clinical trial study designs and regulatory AI middlewares. Droice’s AI middlewares – Droice Hawk and Droice SuperLineage – uniquely automate the preparation of RWD into FDA-compliant submissions with full traceability and inspection readiness. Droice Hawk automates regulatory submission preparation, while SuperLineage ensures full traceability to support regulatory review and inspection.

Learn more about how sponsors partner with Droice Labs to enable efficient, modern clinical trials with submission-ready RWD.